Downtime: A Female Voices Special

As we all look inward and begin to unravel what means most to us, Edinburgh-based writer, Claire Maxwell, shares the documentaries, series’, memoirs, and essays that have irrevocably altered her perspective.

We are supposed to respect our elders. We know that: it’s drilled into us from childhood, from Sundays spent at grandparents’ houses, causing embarrassing scenes by having tantrums about carrots we don’t want to eat or by kicking footballs into beautifully manicured flower beds. We must be on our best behaviour—polite, impressive, just the right amount of vocal. And more than anything, we must listen. There is wisdom to be heard.

I’m not sure I always have though. There’s an arrogance that comes with youth that isn’t entirely our fault, living within a society that celebrates youth so enthusiastically. And the older generations – retired and not always technologically competent – can get left behind in the tailspin of our grandiosity. I remember a family dinner when I was a teenager, sitting next to my great-grandmother who was probably in her late 90s at the time. For, I think, the first time in my life we had a conversation that went beyond the polite and slightly awkward ‘hello,’ ‘how is school?’ and ‘are you feeling better?’. My great-grandmother, a woman who lived until she was 101 and read about the tragedy of the Titanic in the newspaper the morning after it sank, told me about leaving Ireland when she was 18 and getting on a boat, alone, to sail to Canada—probably around the same age as I was then. She chuckled through the stories, her adventurous spirit sparking in her eyes, reminiscing about the violent seas they endured on the trip over. How everyone but her was too sick to eat dinner in the dining room in the evenings. She’d spend the nights making friends with the crew, over tomato soup and bread rolls. I was very impressed. I was an anxious teenager who didn’t like to spend even one night away from my mum. The idea of sailing to a far-off land all by myself was unthinkable.

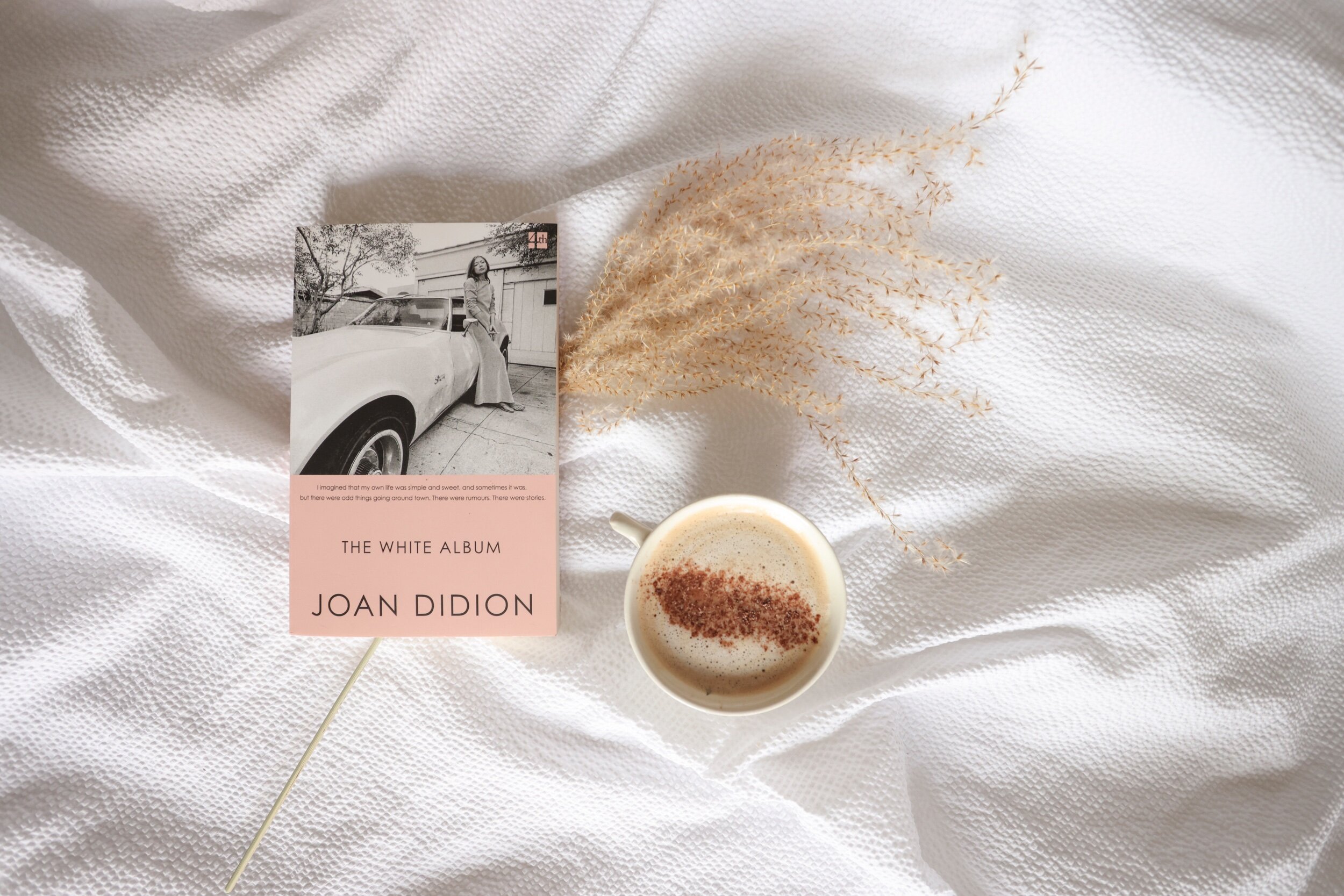

In the last couple of months, what with us being back in lockdown and the weather so miserable, the idea of leaving my flat is, frankly, alarming, I’ve been watching a lot of television. I eked out episodes of Fran Lebowitz and Martin Scorsese’s Pretend It’s a City, and then inhaled the 2017 documentary film about Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold. Both are about women in their 70s and 80s, and both offer insight and perspective that can only come from a few more years in the game (and, albeit, two truly brilliant minds). I like documentaries about writers, artists and public figures in general, but there was something about these two that lingered. I guess the obvious reason why is that Lebowitz and Didion have led such fascinating, varied and cultured lives, but perhaps even more than that: They have an astuteness on subjects both large and small that has the potential to blow a 20-something’s mind (and it certainly did this 20-something).

When I read Joan Didion’s 2005 memoir The Year of Magical Thinking four years ago, I felt irreversibly changed. At the time my dad was ill with heart failure and would later go on to deteriorate and have a heart transplant. The Year of Magical Thinking chronicles Didion’s life and internal monologue after her husband dies of a heart attack. My dad’s medical situation was different but similar, and I read with a knot of anxiety in my stomach until around halfway through when, somehow, Didion’s words started to make me feel secure, reassured, and held, despite the turmoil on the page. There was a wisdom to the methodical way she dealt with the aftermath of such extreme personal tragedy—with reading, and facts, and time, and thought. I listened and what I heard was that even though things can seem overwhelmingly terrible, there is a way to survive and survive we will. I found peace in the chaos of Joan Didion’s words.

In Fran Lebowitz I found permission. She is critical, resistant to change, and her attitude to life, culture, and modernity feels revolutionary to me. Pretend It’s a City explores a plethora of modern topics like wellness culture, technology, house prices, and tourists, and throughout, Lebowitz talks to her friend, the film director Martin Scorsese, about why they annoy her. She’s angry with her fellow man (‘One thing about leaving your apartment is there's so many other people out there. The great thing about my apartment, aside from the fact that it's a great apartment, is that I control if there are other people in it.’); the subway (‘No one in the subway system has any spirit left. They've beaten it out of us. It would take one subway ride for the Dalai Lama to turn into a lunatic.’); and the wellness industry (‘About one third of people in the street in New York City have a yoga mat. That alone would keep me from yoga’). She’s not bitter, she just doesn’t understand—she doesn’t understand why other people don’t seem to think the way she does. In fact, in a recent interview in The Observer she called herself ‘the very essence of reason and logic’. Her lack of self-consciousness and self-loathing – two traits seemingly ubiquitous with the makeup of a millennial woman – is defiant. It looks like freedom.

Both women are writers. They are both so connected to words they are synonymous with the art-form (despite Lebowitz’ 40-year ‘writer’s blockade’). In an essay from her new collection, Let Me Tell You What I Mean, Didion notes, ‘I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.’ And the insights she finds within those words are so deft, so profound, so urgent, we are arguably required to pay attention. She writes of the absurdities that plague our world, about self-respect, writing as a form of self-discovery, memory, and history. She asks questions, interrogates, and shines a light on the path we are all so blindly heading down.

Didion and Lebowitz have lived through the kind of unrest and division that is once again infecting our modern world. When the pandemic hit, calls to listen to those that went through the fear, violence, and rationing of the Second World War (Lebowitz, I’m sure she’d be keen to point out, did not live through the Second World War) were quickly squashed in favour of forging a new path. In Didion’s own words: ‘One of the mixed blessings of being twenty and twenty-one and even twenty-three is the conviction that nothing like this, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, has ever happened to anyone before.’

These women, who’s wit and intellect have comforted and challenged me over the past few weeks of endless doom-scrolling, grey skies and Netflix binging, have bestowed upon us a wealth of their words. Now that I’ve watched the documentaries, I’m hunting down podcast interviews and ordering their books online. It turns out, I can’t get enough.

Follow Claire on Twitter @crudites_